Out of roughly 34,000 traffic-related fatalities in 2009, about one-third involved a driver with a blood-alcohol content of 0.08 or above (the minimum for a DUI offense in every state). Thinking about this I wondered whether this number could be reduced by increasing the penalties for higher BAC levels, since the chances of a collision rise quickly as impairment increases, but fines, suspensions, and jail time do not. After doing some research on the subject, I found instead that this is actually a very complicated issue (surprise!), and my intuition didn't really stand up to scrutiny. Case in point was Wisconsin, a state that already has penalties that scale with BAC but in both 2008 and 2009 had significantly higher rates of alcohol-related fatalities than the national average. Something else is going on here.

Just so you can get a sense for the argument I was making originally, here's the bulk of what I'd written before deciding to add the above disclaimer and what comes afterward:

Idea: drunk driving penalties should be more closely tied to blood-alcohol content

The penalties for a DUI conviction usually include a small amount of jail time, a 30-day to one-year driver's license suspension, and a few hundred to a few thousand dollars in fines--most states also have enhanced penalties which kick in BAC levels of 0.15-0.20. In the case of Washington state, though, the increased penalties for BAC at or above 0.15 don't have much bite: the same maximums for jail time and fines, with barely increased minimums, and a longer license suspension, one year instead of 30 days. Drunk driving of any kind is a serious crime that threatens the lives of the driver, passengers, and anyone else on the streets or sidewalks, but there's a big difference between driving with a 0.08 and a 0.15 BAC. We need to formally recognize this reality, and ensure that the penalty is commensurate with that increased risk.

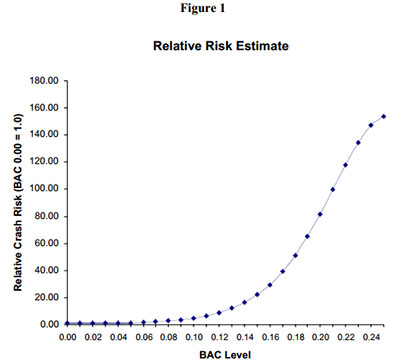

According to this study by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the risk of a crash is 1.74-2.69 times higher at a BAC of 0.08. At 0.15, crash risk is increased by 8 to 22 times, and at 0.20 the risk is 21 to 82 times higher relative to driving unimpaired. (The ranges represent the difference between the study's observed crash rates and its adjustment for those who refused to participate, were involved in hit-and-runs, etc., so the higher number is theoretically the more accurate risk estimate.) So in Washington, even though you're about 30 times more likely to get into a wreck at a BAC of 0.20 compared to 0.08, the punishment hardly differs at all. In the eyes of the law, the severity of each crime is essentially the same. Below is a graph from the study, illustrating the exponential increase in crash risk as BAC increases:

DUI laws in Washington (and many other states, I'm sure) aren't very sensible, but we can look elsewhere for guidance toward a better system. Although I think it still underrates the seriousness of BAC levels much higher than 0.08, Wisconsin has a system that's definitely superior to Washington's. There, penalties double, triple, and finally quadruple as BAC increases. A driver with a >0.25 blood-alcohol content faces penalties four times greater than someone arrested for DUI with a BAC between 0.08 and 0.149, and this includes fines, jail time, and license suspension. Of course, we can see from the above graph that a person with a BAC of 0.25 has a 160-times higher risk of getting into a collision compared to a sober person, and fifty times the risk of a person with a BAC of 0.08, so penalties that are only four times worse (at most) don't really capture the seriousness of driving with a very high BAC.

If BAC-scaled penalties aren't the solution, what is?

Based on the data from Wisconsin, increasing penalties for more serious drunk-driving infractions is not the whole solution. That doesn't mean it can't be a part of it, but it's not enough by itself. So what else can we do? My next thought was that perhaps part of the problem is that, at least in Washington, we so rarely actually convict people of DUIs. I have several friends who have been arrested for DUIs, and all of them were able to plead down to a "wet reckless" with the help of a lawyer, a much less serious crime, even though they blew over a 0.08 on the breathalyzer. Maybe the problem isn't that DUI penalties are insufficient, but that so few people are actually convicted of the crime they've committed.

Nope. Texas doesn't allow defendants to have their charge reduced to a wet reckless, and yet they had even higher rates of alcohol-related fatalities than Wisconsin did. Again though, things aren't so simple: Texas has extremely lax penalties even for a DUI conviction, with no minimum for fines, and as little as 3 days in jail and a 90-day license suspension.

Like I said, this turned out to be pretty complicated (again--surprise!). The most effective solution I found was actually a program that started in Washington state itself in November 2006, and was followed up in 2010. The study was performed in the three biggest counties in Washington and consisted of adding six--yes, just six--state patrol officers to each county, their primary goal being to crack down on alcohol and drug-impaired drivers. The report can be found at the NHTSA's web site [PDF]; it's only 5 pages and I encourage you to check it out for yourself. The gist of the report is captured by the following graph:

The TZTP counties are the three with the extra WSP officers. As you can see, compared to the average over the previous five years, the TZTP counties experienced a 34.4% decline in alcohol- and drug-related fatalities. That's in one year. Compare this to a 28.4% increase in the next two biggest counties (Clark and Spokane), and an 8.5% decline in the rest of the state. It's very possible that the numbers might jump up a bit after people get used to the presence of these extra patrols, but the difference between the pre- and post-TZTP eras is stark and worth investigating further. I have to reiterate once more that this is the result of adding just 18 officers (plus another ten or so support staff) to three counties with a total population of 3.5 million. We could do much more.

During the 10-month window of the study these officers made over 3,000 DUI arrests, 3,000 speeding citations, and 900 seat belt citations. In theory this should mean several million dollars in fines, more than enough to cover the expense of these extra patrols. Due to the leniency of our sentencing, however, I couldn't really guess what we're actually collecting as a result of these arrests. But more importantly than all that, the presence of these officers saved dozens of lives, possibly including the innocent drivers, bicyclists, and pedestrians these drunk drivers might have struck with their vehicles. The fact that it was at essentially zero cost to the state is just icing on the cake.

One way to ensure that we can capture that revenue and keep our drunk-driving patrols funded is to follow in Texas' footsteps (never thought I'd say that) and stop allowing offenders to plea down to wet reckless. Instead of punishing drunk drivers through the justice system's fines and suspensions, we're basically just redirecting that money to DUI lawyers--the people I know that were arrested for DUIs each paid about $5,000 through the whole process, but most of that money went to their lawyers. And for what? What do the lawyers contribute? No one is disputing the fact that these people were driving with a BAC at or above 0.08. The state should collect that money itself in the form of the DUI fines it rarely seems to collect, and use it to fund more patrols instead of enriching a few unnecessary lawyers.

I started this post planning to make a strong argument for increasing drunk-driving penalties, but after starting to write I realized there isn't evidence to back up my claims. Not without controls that don't yet exist, at least. And that's fine. Perhaps not surprisingly, I learned that enforcement seems to be the most effective way to prevent drunk driving and save peoples' lives. These two arguments intersect, however, at funding. If we want to be able to pay for extra patrols, the money needs to come from somewhere, and more strict penalties--or consistent sentencing, at least--could be part of the solution. And as we work to increase enforcement and seek to provide further evidence for its efficacy, let's keep finding new ways to prevent drunk driving, whether that means harsher penalties, more accessible alcohol and drug treatment programs, better transportation options, or all of the above. Even the most incremental improvement can mean hundreds of lives saved over the next few decades, and safer roads for everyone.