A quick note: I wrote a book! It’s called The Affordable City, published by Island Press, and it comes out on September 15th. It’s a how-to guide for affordable housing policies and programs, and it makes the case that truly affordable, just, and accessible cities require us to prioritize Supply, Stability, and Subsidy policies. None by itself will ever be enough. If you’d like to pre-order the book you can do so HERE using the promo code “PHILLIPS", or you can sign up for my mailing list to be notified when it’s officially released. Thank you!

Transfer tax reform, including higher rates assessed on the biggest beneficiaries of Proposition 13, could raise approximately $1.85 BILLION per year for the City of Los Angeles — a more than 15% increase to the city’s total annual budget.

Last week I published a new report at the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policies titled “A Call For Real Estate Transfer Tax Reform.” In it, I recommend that the City of Los Angeles — and other cities — establish graduated taxes on the sale and transfer of real estate, with higher rates on more valuable properties. Transfer taxes are progressive, they function as a tax on wealth, and they’re easy to calculate and easy to pay. Currently most cities in California assess a flat transfer tax of about 0.5% on the sale price of properties, and in the City of LA our transfer tax raises just $212 million per year. San Francisco, which has less than a quarter our population, raises $368 million.

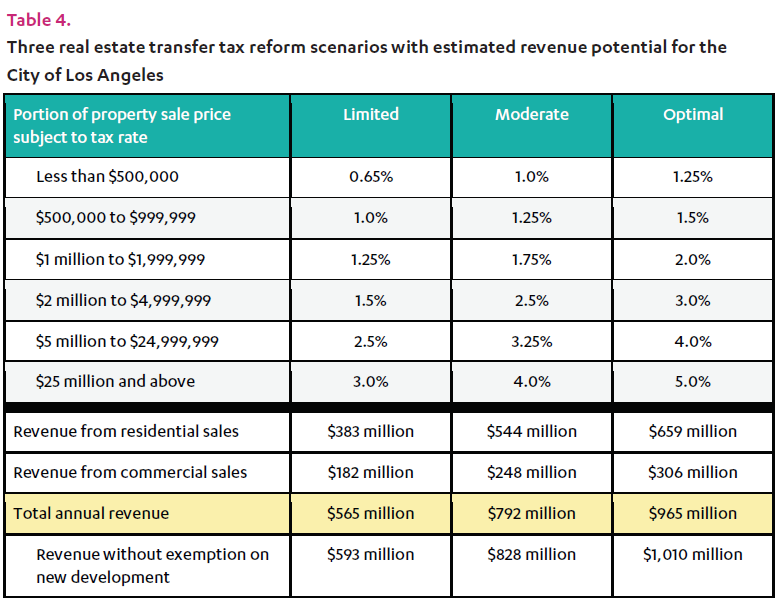

The main takeaway from the report is that a graduated, marginal transfer tax could raise between approximately $600 million and $1 billion per year, 3-5 times what it raises today and approaching 10% of the city’s entire budget. It’s big money that can do a lot of good, and the people paying it won’t really miss it. Here’s a table from the report showing the revenue potential under three separate scenarios (I recommend “Optimal,” of course):

A basic graduated transfer tax could raise approximately $1 billion in annual revenue for the City of LA, up from about $210 million today.

I encourage you to read the full report if you haven’t already, but in this post I’d like to discuss a more specific recommendation: Assessing higher transfer tax rates on sellers with lower effective property tax rates. In other words, using transfer taxes as a way to reverse some of the inequitable outcomes of Proposition 13.

Prop 13, for the uninitiated, was a 1978 anti-tax (and racially-motivated) ballot initiative which capped property taxes at 1% of assessed property value and limits annual assessment increases to 2% per year for as long as a person owns their property. The initiative was sold as a way to protect homeowners from runaway tax assessments, which were a legitimate problem, but the end result has been a deeply inequitable tax structure that’s essentially created a landed gentry in California, with the benefits flowing disproportionately to older, whiter, wealthier households. It also limits household mobility, discourages redevelopment of vacant and underutilized parcels, and starves the government of revenue from those best situated to pay. It sucks.

Reforming Proposition 13 is notoriously challenging. Property owners are heavily invested in maintaining their tax subsidies, even if they come at the expense of everyone else (and they do). Years ago I proposed a compromise policy that would assess taxes on the full property value, but defer collection until the property is sold, but I didn’t actually have much hope that something like this could pass. Transfer taxes might actually help us achieve that goal.

TRANSFER TAX MULTIPLIER

By assessing higher transfer taxes on the sale of properties with lower effective tax rates, we can recapture some of subsidies wastefully showered upon certain California property owners. The idea is to apply a multiplier to the transfer tax payment based on the seller’s effective property tax rate. The effective property tax rate is simply the assessed property value (prior to sale) divided by the sale price, then multiplied by the 1% property tax rate. A property assessed at $500,000 and sold for $1.5 million, therefore, has an effective property tax rate of 0.33%.

The multiplier would grow as the effective property tax rate fell. If the effective property tax rate was 0.9% or higher, the multiplier would be 1.0 (no multiplier, in other words). If the effective tax rate was between 0.8% and 0.9%, the multiplier would be 1.2. This would continue all the way down to effective tax rates under 0.1%, which would receive a multiplier of 2.8. I think these numbers are reasonable, but there’s plenty of room for debate about whether they should be higher or lower.

Under the “Optimal” scenario in the report, a property sold for $1.5 million would pay a transfer tax of $23,750, or 1.58% of the sale price. If it were assessed for just $500,000 at the time of sale, and therefore paying an effective property tax rate of 0.33%, the transfer tax payment would be subject to a 2.2x multiplier. The total payment required would then be $52,250.

I estimate that the “Optimal” transfer tax scenario, paired with a multiplier on properties with low effective property tax rates, could raise approximately $1.85 BILLION per year for the city, more than 15% of the city’s total annual budget. This is in comparison to the city’s current projected transfer tax revenues of $212 million and my estimate of $1 billion per year under the Optimal scenario without the multiplier.

Is this unfair to long-term property owners? Absolutely not. If anything it doesn’t go far enough, but it’s a big improvement over the status quo. For an example, take this home in Westchester, just north of LAX:

This home was purchased in 1993 for $285,500, then sold 26 years later for $1.28 million. At the time of sale it had an assessed value of $434,990, which is about one third of the sale price — an effective tax rate of 0.34%. Over the 26 year ownership period, the assessed value increased by an average of 1.63% per year. The actual value, based on the sale price, grew by an average of 5.94% per year.

Over that time, because of Prop 13 restrictions on taxable value, the owners paid about $96,000 in property taxes. If their taxes had increased at the same rate as their estimated property value (i.e., what they could have actually sold the property for, not just the assessed value), they'd have paid roughly $180,000 in property taxes — $84,000 more. That’s an $84,000 discount given to a property owner simply for retaining ownership of their property for a long time, irrespective of their income, wealth, or any other individual circumstances. Here’s what that looks like year by year:

The base transfer tax payment at the time of sale under the Optimal scenario is $23,750. The 2.2x multiplier adds another $28,500. To put a very fine point on it, $28,500 is less than $84,000. It’s even less than that once you adjust for inflation, since much of the foregone property tax revenue was incurred decades ago, when a dollar went a lot further. This proposal doesn’t fix the inequity entirely, but under LA City and County’s current combined transfer tax rate of 0.56% this $1.28 million property paid a transfer tax of just $7,168. Increasing the payment to $52,250 is a big improvement.

And let’s not forget that the increased property taxes the owner would have paid, in lieu of Prop 13, only occurred due to rapid home value appreciation. Over 26 years their property’s value quadrupled, growing by $900,000. The transfer tax is paid from those profits and only exists because of those profits. It’s value that all Angelenos, collectively, had a hand in creating, and it’s reasonable for us to capture a share for the collective benefit.

NEXT STEPS

Some California cities, including Oakland, Berkeley, Emeryville, and San Francisco already have graduated transfer taxes that are considerably higher than those found anywhere in Southern California. All of these cities approved their increased taxes via ballot initiative in the past six years, and all received support from roughly 60% of voters or more (Berkeley’s got 72.4%). These cities, if they wish, may start organizing around a transfer tax multiplier right away.

For cities like Los Angeles, which don’t yet have a graduated transfer tax in place, some caution is probably warranted. Based on the track record of Bay Area cities and a recent Santa Monica survey showing 62% support for a transfer tax (the city rejected a similar initiative in 2014 with 58% opposed), passing a basic graduated transfer tax seems very possible in Southern California. Probable, even. Without ever testing the proposal at the ballot, or even with a survey, complicating the initiative with a complex “effective property tax rate multiplier” is probably too risky. I recommend we start with basic transfer tax reform in 2020 then try a multiplier in 2022 or 2024.

Overall, this is a great opportunity to recapture some of the wealth we’ve funneled to property owners, and property owners alone, for the past four decades. Transfer taxes already have a lot of benefits, and paired with a property tax multiplier they can do even more.