This is a fairly minor follow-up to the post I wrote a few months ago about the pointlessness of the mortgage interest tax deduction. This is about the property tax deduction. Like the MITD, the PTD does a poor job of achieving its supposed policy goals, and in some cases actually works at cross-purposes to those goals.

Just as with mortgage interest, property owners are able to deduct state and local property taxes from their taxable income. Rental property, like owner-occupied housing, is also subject to this exemption. The goal of mortgage interest and property tax deductions is nominally to encourage homeownership, but by it's very nature this can't happen with rental property. Instead, all we end up doing is taking money out of the pockets of renters and handing it over to the (on average, richer) owners, with no social or economic policy victories to speak of.

Here's why:

Rents will usually be set by landlords at whatever level the market will bear (i.e., the highest level at which they can still rent all of their units). Unless competition for renters is extremely fierce, these property owners will be charging rents that cover their costs--not just their mortgage, but also repairs, landscaping, cleaning, taxes, and hopefully some profit. Renters, although they don't receive the actual bill, are the ones paying the property tax as part of their rent checks. Despite this fact, however, the property owner is the one who gets to write it off.

This means that if the property tax bill on my rental unit is $2,000 every year, I end up sending that money to my landlord (who then forwards it along to the city and state) and he deducts it from his taxable income, saving him upwards of $500. That's a pretty steep middleman's fee. The deduction is very clearly not succeeding at its goal of "encouraging homeownership". After all, I'm still renting. Maybe if I got to keep that extra $500 myself I'd be a little closer to owning a home. At the very least, we're clearly operating under an unfair system when only homeowners can deduct their property taxes even though both renters and owners pay them.

This isn't the fault of the property owners and I am not writing this with some kind of vengeance in mind for them, but if the deduction isn't helping to encourage homeownership* then why does it exist? From a government policy perspective, property and mortgage interest tax deductions are already of very questionable value for owner-occupied housing; in this case it's nothing more than a giveaway to rental property owners with nothing in return for the renter or society more broadly. No good is achieved.

As I wrote in November, there's no need for any additional incentive to purchase a home. Unless we want to find some way to ensure that the deduction finds its way into the hands of the person who actually paid the tax, we're better off getting rid of it entirely.

(I'd be interested in anyone's thoughts on how we might pass along the property tax directly to renters, or more likely give them the option of doing so. At first glance it seems too complicated to be worthwhile, and just getting rid of the deduction seems like a more realistic solution. But maybe there are some good ideas out there.)

*Other than in some perverse "force renters to overpay on their taxes until they wise up and buy a house" fashion.

Parking-free apartment buildings aren't enough

In Portland some developers have recently started constructing apartment buildings without parking (a practice that is illegal in most cities), angering some neighbors who complain that the tenants still own cars, and that they just park them on the street instead of in privately owned spaces. And they're right. According to an article in the Oregonian:

[The city] found that 73 percent of 116 apartment households surveyed have cars, and two-thirds park on the street. Only 36 percent use a car for a daily commute, meaning the rest store their cars on the street for much of the week.

Frankly, this is pretty damning evidence that parking-free apartment units don't actually discourage car use. Not enough, and not by themselves, at least. Of course, only 73% of households owning a car is far below the average rate of car ownership in most cities, but it's still the majority of the tenants. What I found most significant here was the fact that only 36% use their cars for commuting--half of the households that own a car. The implication, of course, is that with the right incentives many of the people who don't commute with their vehicles could be encouraged to get rid of them. In the age of ZipCar and walkable cities, owning a car in this type of environment is more a matter of inertia than genuine need.

What might those incentives look like? One option might be for property managers to offer access to car-sharing, as is being done in a few places throughout the country. This might also be something cities themselves, or a non-profit of some kind, could administrate. For example, in exchange for donating your car you might get a five-year membership to a car sharing service with up to 20 hours of use a month. The value of getting people out of their cars is so high for cities--less congestion, pollution, and carnage, and considerably more money spent locally--that subsidizing some of the cost of car sharing might even be worthwhile.

Another obvious incentive is appropriately pricing our existing public parking spaces. In my old neighborhood of Capitol Hill, and many of the busier areas of the city, a parking permit is required to park on residential streets during the day, and costs $65 every two years. On commercial streets we're currently asking drivers to pay up to $4 per hour to park, but our residents aren't even paying $4 a month! And as far as I can tell there doesn't even seem to be a limit to how many you can purchase beyond, presumably, the number of cars you own. We set prices for commercial parking to ensure that those willing to pay can always find a space, but don't adhere to this philosophy when it comes to residential parking.

The same residents paying effectively nothing (usually actually nothing, for most neighborhoods), are demanding that developers--and hence the residents of those new developments--foot the bill of $10-20k (and upwards of $50k in some places) per parking space, usually underground. In other words, only existing residents get free parking, and everyone else has to pay the full cost. Even those who don't drive end up paying, in the form of taxes used to build and maintain the public roads being used for car storage. At a time when we recognize that reduced car use is good for cities and good for people, why are non-drivers subsidizing the cost of vehicle storage, and single-car households subsidizing multi-vehicle households?

A drastic increase in the cost of parking permits would raise considerable revenue, but I'd be perfectly content if it was dedicated to nothing but road maintenance. The real goal is a resolution of the Tragedy of the Commons, wherein un-priced public goods (in this case parking spaces) leads to vast overuse, harming everyone in the process. Revenue is simply beside the point. Even if a change in parking permit prices was offset by a slight decrease in, say, local sales taxes, making it completely revenue neutral, it would be a huge boon to the awful parking situation in the city, and to our economy.

The point of all this is that it would also discourage people in the densest, transit-oriented parts of the city from owning cars that they only use for occasional trips. For current residents who own a car and don't want that purchase's value completely destroyed by the increased cost of parking, the trade-in for a ZipCar-like subscription could help mitigate that loss. This, or another creative means of positively incentivizing a switch to a car-free or car-lite lifestyle, would be a valuable and perhaps necessary complement to increasing long-term parking costs.

Even if all the new developments in the city provided enough parking for their residents, there's a critical point at which our roads simply can't handle any more traffic. We need to pair strategies for reduced parking in new apartment buildings with strategies to reduce car ownership and, especially, reduce the need for it. Doing just one or another won't be enough.

Let's get rid of the mortgage interest tax deduction--for everyone

The mortgage interest tax deduction is a giveaway to wealthy households to help them buy bigger housing, and provides almost no benefit to lower and middle income households. We should stop worrying about tinkering around the edges and abolish it altogether.

Read MoreIncreased apartment housing in Seattle likely to stabilize rent prices

It's a common refrain among urbanist types who are savvy to land use issues that increasing the amount of housing in a region can lower rents, or at least slow their rise. The reasoning is straightforward: if you have more demand than supply, prices will increase; if you increase supply to meet or exceed demand, landlords will be forced to compete with one another for renters and prices will decline.

This sounds really great. When you combine it with all the other great things densely-built, transit-oriented development can bring (more walking, bicycling, and transit use; more efficient use of energy and infrastructure; greater diversity of shops, restaurants, and entertainment; more spontaneous interactions with other members of the community; etc.), it sounds even better. But is it true? Do rents really decline just because more units of housing get built? I wanted proof.

After reading this article at the Seattle Times on the boom in apartment building in the Puget Sound region and the effects it may have on rents, I felt like I was on the right track. Unfortunately, the most conclusive statement contained in the article in support of this idea was the following:

[T]he regional apartment-vacancy rate has stopped dropping, both Dupre + Scott and Apartment Insights say, and it should start inching up next year as a bumper crop of new apartment projects comes to market.

That means “rents will basically have to flatten out,” said Mike Scott of Dupre + Scott.

Great news! Not exactly a scientific proof, but I'll take it. Near the end of the article, however:

Even so, 73 percent of landlords responding to that company’s survey said they plan to increase rents over the next six months.

Okay, not so good news. Most of the 35,000 units planned for the next 5 years haven't opened yet though, so maybe landlords are just getting what they can while the gettin's good. Soon enough, the thinking goes, the balance of power is going to tip back toward the renters, and prices will moderate. And a good thing too, since in-city rents for 20+ unit apartments in Seattle have increased by almost 7.5% in the last year (most of that, 6%, in the last 6 months). Has this actually happened? Thankfully, the Times article led me to the answer.

In an article Dupre + Scott Apartment Advisors have produced to accompany the aforementioned survey, they clearly describe some of the trends in the region and break it down into sub-regions with some nice charts. I really encourage you to read the whole thing--it's not too long. But first, and most importantly, I'd like to show you the following two charts from the article:

What I hope you'll appreciate when looking at these charts is their opposing nature. When vacancies are low, rents go up; when vacancies are high, rents go down. That's right, they actually went down! Next time someone tells you it's not possible, and asks you how building new, usually more expensive housing will lower rents, just point them here. It works. And just to be clear, I believe these prices are in nominal terms, not inflation-adjusted, which would explain why prices tend to increase by higher percentages than they decrease. If you provide enough housing to affect vacancies (i.e., enough to meet or exceed demand), prices will go down.

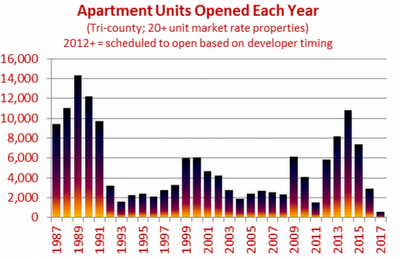

Now I'd like to point out one more chart:

Note how many apartment units were opened in 1999-2002, and then take a look at the vacancy rate for 2001-2005 in the earlier chart. We built a lot of units in that time period, and it seems that this had a significant impact on the market vacancy rate. If you know of something else that accounted for this difference please let me know in comments, but for now I'm going to stick with the sensible conclusion that the supply increased beyond demand and we ended up with a bit of an apartment glut. Prices went down and all was right with the world (for renters, at least). Now look at how many units are planned for 2012-2015. Many more! I suspect that demand for urban living has increased since the early 2000s, but nonetheless this bodes very well for apartment prices in the coming years. And just to drive the point home, note that it took a year or two after the apartments started coming online for prices to start declining. That shouldn't be surprising since the first to open probably only served to soak up the existing unsatisfied demand for living in the regions--it took an excess of supply to actually start bringing prices down.

One more thing to look forward to, renters: besides the large addition of apartments we're experiencing, the real estate market is also improving. That means many people who were forced into renting, or delayed buying a house until they were certain the real estate market had hit rock bottom, are going to start exiting the rental market. So look for this to remove some of your competition as well, driving prices down even further.

So three cheers for providing more housing in Seattle! It's efficient, it's in demand, and it helps keep housing affordable. What's not to like!?